Photo by Hasan Almasi on Unsplash

In his 1978 speech, “How to Build a Universe That Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later,” science fiction writer Philip K. Dick (who wrote the book that became the movie Blade Runner) wrote, “The basic tool for the manipulation of reality is the manipulation of words. If you can control the meaning of words, you can control the people who must use the words. George Orwell made this clear in his novel 1984.” Forty-five years later we find ourselves living in a world where perhaps most of the conflicts in public discourse are somehow connected to the manipulation of words.

Suddenly, words like “gender,” “racism,” and “equity” don’t mean what they used to mean. Meanwhile, our ears and social media accounts are bombarded by new terms like “microagression,” “intersectionality,” and “cultural appropriation.” If it seems as though other worldviews are wrestling for control of the English language’s steering wheel that’s only because they are.

“Haven’t you heard it’s a battle of words?”1From “Us and Them,” song by Richard Wright and Roger Waters, from Dark Side of the Moon, by Pink Floyd, 1973. I previously used this part of that lyric as a section heading in “Identity Wars: Christ and Culture,” Dec 9, 2021.

It should come as no surprise that today’s word manipulators gravitate to terms that carry maximum impact on hearts and minds. This is true whether they’re coining new terms or plundering old ones. As Robert J. Lifton explained long ago, people who practice this, whom he called “totalists,” “live in an environment characterized by the thought-terminating cliché.”2Robert J. Lifton, Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of “Brainwashing” in China, New York, NY, USA, and London, UK: W.W. Norton & Company, 1963, 429. They conscript words and phrases into the service of their ideology, strip them of their former identities, shave their heads, and put them in new ideological uniforms. In the war of ideas, words are the boots on the ground. They must be drilled into disciplined troops.

Does the reigning ideology require that the LGBTQ+ agenda be accepted by Christians? Then positive, inviting words like “affirming” must be drafted into service and applied to those churches who cooperate with that agenda. Those who don’t are obviously “haters” and “bigots.” (These are but early assault troops paving the way for the full-on invasion of elite forces like “gender non-conforming,” “transphobia,” and “lived experience,” thus signaling that the occupation is fully underway.)

But what if the other side mobilizes its own time-tested terminology in defense of its opposing beliefs? For example, how does the ideology defend itself against a word like “heresy?” Obviously, that word must be captured, re-educated, if you will, and assigned to its appropriate place on the battlefield.

“LGBTQ+? Where do the early creeds even mention that?”

One of the most common ways of doing that with the word “heresy” is to limit its firepower. To slightly mix metaphors here, throughout church history “heresy” has served as a kind of “military assault weapon,”3I am using this term facetiously. I’m not here condoning it as a legitimate name for any rifle with respect to current debates over the 2nd Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. if you will, in theological battles. In a far less tolerant time, countless people were executed, often rather gruesomely, for heresy.

Of course, for the past few centuries the worst thing that can happen to most people accused of heresy is that they might have to find another place to go to church. Even so, that is now considered cruel and unusual punishment in the rhetoric of today’s ideologues (who will gladly “cancel” you out of your career and social circle if you step out of their prescribed verbal line).4Cf. R.C. Sproul, “None Dare Call It Heresy,” April 1, 1994, Ligonier.

So, in recent years, many have tried to retool the weapon of the word “heresy” to degrade its functionality. They realize they can’t scrap it altogether, so they try to rebuild it with a much shorter range and less ammunition capacity, mainly so that it can’t be effectively used against them.

Perhaps the most popular way of doing this has been to limit the number of doctrines that “heresy” is able to target by insisting that it can only be applied to a limited set of doctrines—specifically, those doctrines that were established within the first half-millennium of the Christian church concerning the Deity of Christ and the Trinity, specifically at early church councils like the one that produced the Nicene Creed, which is still recited in many churches. This way, they can claim that current controversies over issues of sexual morality have nothing to do with heresy.

I once had a pastor in my own denomination tell me, “Heretics deny Nicea, not Westminster,”5This was a comment directed at me on July 28, 2017 in a private Facebook group. the Westminster Confession of Faith being one of our denominational standards affirming such things as the sole authority of Scripture and justification by faith alone, which are not found in the Nicene Creed. He couldn’t be more wrong.

If they can fool educated, conservative, Bible-believing Christians into accepting this canard, they will have effectively disarmed them of an important weapon in the battle over the teachings of God’s word.

A Recent Example

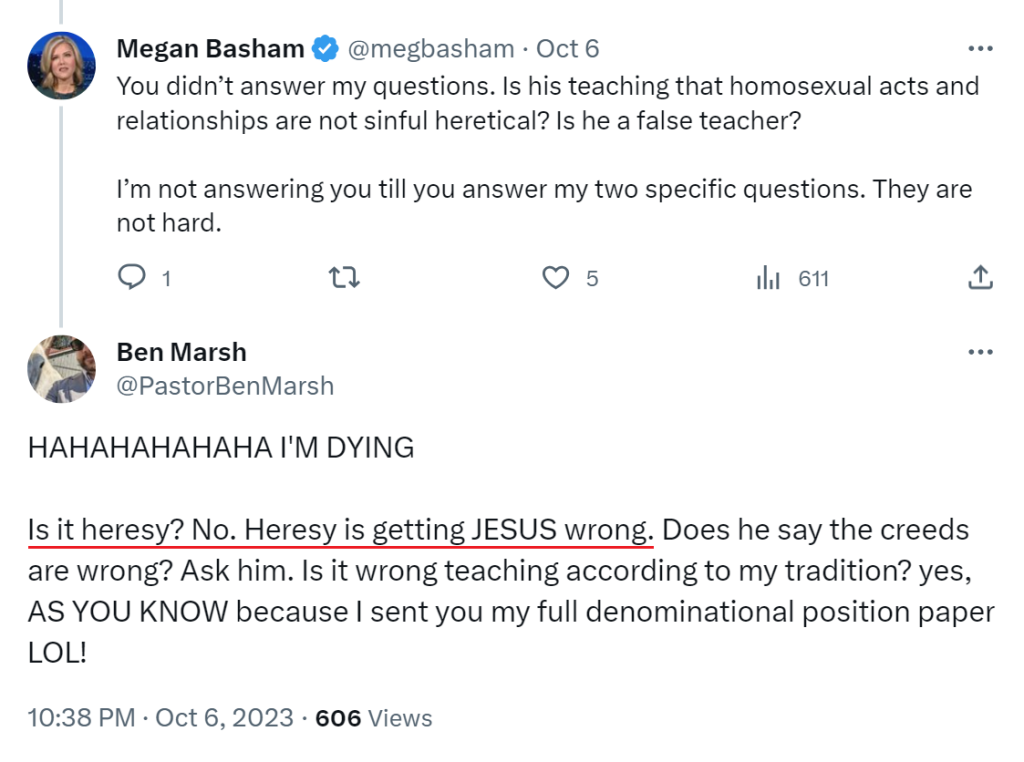

Several days before I wrote most of this on the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, i.e., X, Megan Basham called out LGBTQ+ “affirming” pastor Kevin M. Young for “his heresies regarding sexuality.”6https://x.com/megbasham/status/1710475865820111157?s=20. Two minutes later, Christian and Missionary Alliance pastor Ben Marsh upbraided her, telling her to “get a life.”7https://x.com/PastorBenMarsh/status/1710476509876572320?s=20. Less than a half-hour later, Basham asked Marsh to tell her “whether what Kevin Young teaches about homosexuality and transgenderism is heresy, which led to the following exchange a few minutes later:

This is but a variation on the common myth I summarized above: limiting the definition of “heresy” to the doctrines of the Deity of Christ and the Trinity as defined by the early church creeds. Marsh has shallowly summarized this as “getting Jesus wrong,” but I’ll stick with his His error is easily corrected with a modicum of investigation. I’ll try to provide a bit more than that here to show that historically, the words “heresy” and “heretic” generally have not been either defined or used in the limited sense of “getting Jesus wrong.”

A Brief History of the Word “Heresy” in the Christian Church

On the contrary, when 12 articles of indictment for “heresy” were lodged in Rouen, Normandy against 19-year-old Joan of Arc (c. 1412-1431) for claiming to have received revelations and visions from God as the basis for becoming a military leader during the Hundred Years’ War, not a single one of them had anything to do with “getting Jesus wrong.”

When Leo X issued his papal bull, Exsurge Domine (“Arise, O Lord”) on June 15, 1520, charging Martin Luther with 41 “errors [that] are either heretical, false, scandalous, or offensive to pious ears, as seductive of simple minds,” none of those “errors,” even the “heretical” ones, had anything to do with “getting Jesus wrong.”8“Exsurge Domine, Condemning the Errors of Martin Luther, Pope Leo X – 1520,” Papal Encyclicals Online.

And when the Council of Trent (1545-1563) met to condemn the Protestant Reformers who affirmed all the same Christological and Trinitarian doctrines they did, those Roman Catholic bishops had no problem applying the word “heretics” to them on issues that had nothing whatever to do with “getting Jesus wrong.”9E.g., “Wherefore, having been, as we have said, called upon to guide and govern the bark of Peter, in so great a tempest, and in the midst of so violent an agitation of the waves of heresies…” [bold style added], from “The Bull of Indiction of the Sacred Ecumenical and General Council of Trent under the Sovereign Pontiff, Paul III,” Papal Encyclicals Online.

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church nails it when it defines “heresy” as “The formal denial or doubt of any defined doctrine of the Catholic faith.” 103rd ed., Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1997, 758; emphasis added. “Any defined doctrine” is not limited to “getting Jesus wrong.”

Likewise, the Evangelical Dictionary of Theology supplies perhaps an even broader definition, “…an unorthodox opinion held by a group—sometimes even a majority—within the church.”11Walter A. Elwell, ed., Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, 2nd ed., Grand Rapids, MI, USA: Baker Academic, 2001, 550.

Meanwhile, the Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms is careful to provide two entries, one for “heresy,” and the other for “heresy, christological.”12Donald K. McKim, The Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms, 2nd Edition, Revised and Expanded, Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2014, 145. Obviously, only the latter is about “getting Jesus wrong.” The word “heresy” alone is not.

And consistent with all the above, the Pocket Dictionary of Theological Terms defines “heresy” as “Any teaching rejected by the Christian community as contrary to Scripture and hence to orthodox doctrine.”13Stanley Grenz, David Guretzki, and Cherith Fee Nordling, Pocket Dictionary of Theological Terms, Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1999, 58; emphasis added.

In all likelihood, the current myth that “Heresy is getting Jesus wrong,” which pops up from time to time, can be traced back to the Second English Act of Supremacy of 1558 (sometimes titled 1559, the year of its approval), which was part of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement under Elizabeth I which reestablished Protestantism as the faith of the Church of England following the reign of Mary I (Bloody Mary). It declared that anyone acting under the authority of the monarch,

…shall not in any wise have authority or power to order, determine, or adjudge any matter or cause to be heresy, but only such as heretofore have been determined, ordered, or adjudged to be heresy, by the authority of the canonical Scriptures, or by the first four general Councils…or such as hereafter shall be ordered, judged, or determined to be heresy by the High Court of Parliament of this realm, with the assent of the clergy in their Convocation…14Gee, Henry, and William John Hardy, eds., Documents Illustrative of English Church History, (New York, NY, USA: Macmillan, 1896), 455

The “first four general Councils” to which the Act refers are the ones that established orthodox Christology and Trinitarianism for the church: First Nicaea (AD 325), First Constantinople (381), First Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451). These are the councils that defined what it means to “get Jesus right.”

In the wake of the Marian martyrdoms of Protestants, this limitation on the definition of “heresy” was provided with “the intention of preventing any future persecution of Protestants” 15Claire Cross, “Orthodoxy, Heresy and Treason in Elizabethan England” [«Orthodoxie, hérésie et trahison dans l’Angleterre élisabéthaine»], Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique, [French Journal of British Studies], XVIII-1 [2013]. Giving Parliament a large say in the determination no doubt helped assure that. But one could imagine that it would also potentially have a calming affect on any remaining Roman Catholics in England at that time as under this Act they could not legally be charged with heresy over differences on the doctrine of salvation.

In any case, limiting the definition of “heresy” to the first four councils (which “got Jesus right”) was a specifically Anglican development, rooted in the religious politics of the 16th century (as virtually all the confessions, catechisms, and other official Reformation and Post-Reformation documents were). It had a specific practical goal for the English situation.

Other branches of Protestantism did not allow themselves to be bound by this definition, much less did Roman Catholicism. For example, the 1618-1619 Synod of Dort didn’t hesitate to refer to “the proud heresy of Pelagius” (Canons of Dort 3/4, Art. 10), even though Pelagianism is not a Christological heresy and was not addressed by the first four councils.

During the proceedings of the Westminster Assembly (1643-1653), English theologian Cornelius Burges (c. 1589-1665) reminded his colleagues “that Elizabethan statutes defined heresy by that which contravened the creeds of the four ecumenical councils or that which was determined to be heresy by parliament.” 16Chad Van Dixhoorn, ed., The Minutes and Papers of the Westminster Assembly 1643-1652, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2012, 1:22.

But another delegate to that Assembly, George Gillespie (1613-1648) took no notice of this limitation when he sought to arrive at a Scriptural definition of “heresy.” Surveying the biblical data and noting that our word “heresy” comes from the Greek αἱρέσεις (hairésis: 1Co 11:19; Ga 5:20; 2Pe 2:1), he wrote:

“From all which scriptural observations, we may make up a description of heresy to this sense: ‘Heresy is a gross and dangerous error, voluntarily held and factiously maintained by some person or persons within the visible church, in opposition to some chief or substantial truth or truths grounded upon and drawn from the Holy Scripture by necessary consequence.’”17George Gillespie, “A Treatise of Miscellany Questions,” Chapter IX., “What Is Meant in Scripture by the Word Heresies…” in The Works of Mr. George Gillespie, Edinburgh, UK: Robert Ogle and Oliver and Boyd, 1846, 2:49

No “Soft Middle Ground”

And this has been its generally accepted meaning throughout church history. The “getting Jesus right” definition is an historical outlier, although you wouldn’t know that from the groundless confidence with which its advocates assert it.

Thus, it should come as no surprise that the false doctrine regarding circumcision in the early church has been called “the Galatian heresy” since at least the early 19th century even though it had nothing to do with Christology. And regardless of whether the antinomianism against which Peter, John, and Jude contended had any Christological dimensions, it too was a heresy by the commonly accepted historic definition.

Which leads directly to the current strain of antinomianism known as “gay” or “affirming Christianity,” an obvious anti-Christian heresy if there ever was one. If any of the authors of Scripture were alive today, they would no doubt absolutely condemn it in the strongest terms, saving many of their harshest words for heretics like Kevin M. Young who eagerly spread its poison, and not withholding severe warnings from the likes of Ben Marsh who brazenly mocks faithful Christians like Megan Basham for taking no part in the unfruitful works of darkness but instead exposing them (Ep 5:11).

Christians cannot stand in some soft middle ground on this issue. It doesn’t exist. Countless souls are passing into the damnation of a Christless eternity each day because of it. Wake up!

For it is time for judgment to begin at the household of God; and if it begins with us, what will be the outcome for those who do not obey the gospel of God? (1 Peter 4:17 ESV)Ω

© 2023, Midwest Christian Outreach, Inc All rights reserved. Excerpts and links may be used if full and clear credit is given with specific direction to the original content.

Mr. Henzel, You have done it again, with a very thoughtful and helpful review of the meaning of heresy, reaching beyond the importance of orthodoxy in Christology, to orthodoxy, and orthopraxy in biblical morality!

Good article! I suggest most are illiterate, especially the young in Christian dome. Which Jesus is the ‘getting Jesus wrong’ does Marsh worship (a false god)? I never heard that saying before, I suggest she is uncorrectable (an abomination). The word Abomination I don’t hear anymore. Occurring 79 times in the KJV in 69 verses according to Strong’s. ‘Thou shalt not lie with mankind, as with womankind: it is abomination.’ Leviticus 18:22. ‘a disgusting thing, abomination, abominable’ #H441. ‘If a man also lie with mankind, as he lieth with a woman, both of them have committed an abomination: they shall surely be put to death; their blood shall be upon them.’ Lev. 20:13

‘The graven images of their gods shall ye burn with fire: thou shalt not desire the silver or gold that is on them, nor take it unto thee, lest thou be snared therein: for it is an abomination to the LORD thy God.’ Deut. 7:25. ‘For the froward is abomination to the LORD: but his secret is with the righteous.’ Prov. 30:42. ‘He that turneth away his ear from hearing the law, even his prayer shall be abomination.’ Prov. 28:9 ‘And there shall in no wise enter into it any thing that defileth, neither whatsoever worketh abomination, or maketh a lie: but they which are written in the Lamb’s book of life. Rev. 21:27. You could in these last days go to jail for quoting these words, is that not an abomination? Blessings~ Psalm 111:10.

Hey Ron

Great article!

In the battle of words todays saying is “if you can’t beat them, baffle them with… you know the rest.

How can someone who behaves the way Marsh does on X actually be a pastor? Disgraceful.

The Great Commission, a command given from our risen Lord to His disciples, to make more disciples, was, “[teach] them to observe all that I have commanded you”

I have taken “heresy” to mean any teaching which breaches this command, since this command covers…everything.